In a little-used portion of the Wagin Cemetery, surrounded by weeds struggling to survive in the dry brown soil, is a grave, bordered by a rusted iron railing atop concrete kerbing. All that can be read on the memorial plaque in the centre of this lonely rectangle are the words, ‘Kathleen’ and ‘November 1918’.

The woman who lies buried in this grave is Catherine Grace Hinnigan and hers is but one of the many stories linked to the signing of the Armistice, 100 years ago.

Roman Catholic Section - Lot 56. Wagin Cemetery

In the final months of 1918, the fifth year of the Great War, a rising sense of hope was evident amongst the war-weary allied troops on the Western Front. Bulgaria had surrendered to the Allies in October and Turkey and Austria-Hungary followed suit early in November. All that was needed was Germany to agree to an Armistice and this seemed imminent with the Allied army breaking through the German lines, reducing their forces to a state of collapse.

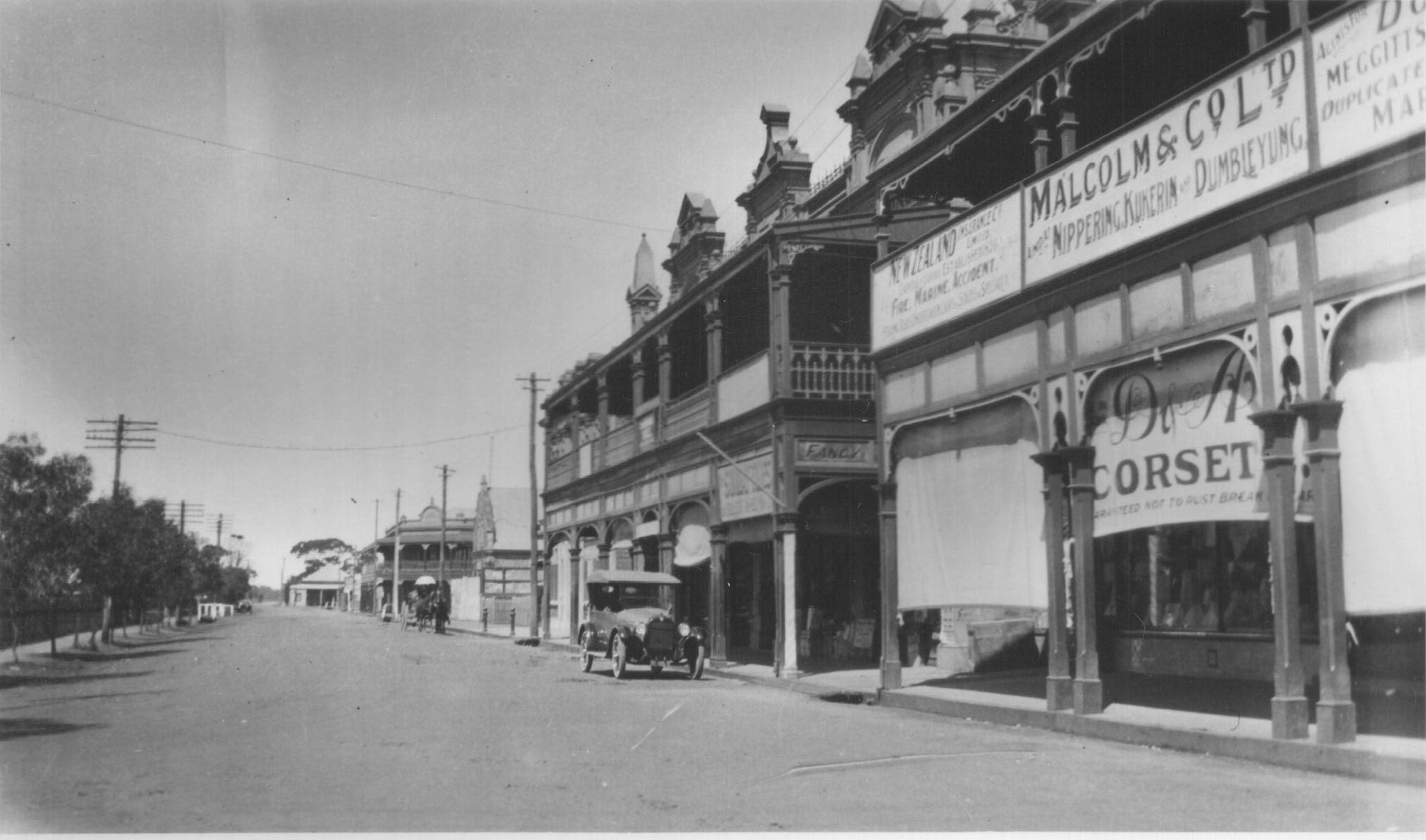

A world away in Wagin, a small country town in Western Australia’s Great Southern Region which relied on the surrounding wheat and sheep farms for its existence, excitement was building. The newspapers, for so long full of casualty lists, reports of battles lost and dire predictions were, at last, carrying articles predicting a cessation of the fighting. The prospect of peace and an end to the hostilities was infectious; an impromptu celebratory procession through the streets of the town on Friday 8th November was organised.

My mother, then aged six and a half, accompanied by her sisters and my Gran took part in that parade. They’d moved to Wagin from Fremantle in 1914, a few months before my grandpa enlisted and sailed off to war.

Some seventy-five years later, my mother recalled that procession in a recorded conversation. I’ll let her tell the story……

"I can remember also when Armistice was declared, when we'd won the war. We had a procession; everybody went mad in this procession down through the streets of the town and one lady in the procession dropped dead and she had, as well as little baby, she had other children and I think she got so excited she must've had a weak heart or something. She had a baby in a pram - she just dropped dead in this procession it was somebody that I knew, I can't tell you the name. Mum knew - everybody knew, well everybody knew everybody in those days, in those situations. It was a dreadful thing."

Over the years, I’d heard this story many times when I listened to my Mum’s taped reminiscences but never paid it much attention. Now, however, with the looming Centenary of the Armistice, I was intrigued. Had Mum remembered correctly - who was the lady?

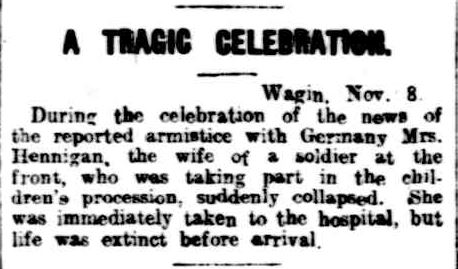

The West Australian of the 9th November was the first newspaper to carry the story, a small item published the day after the procession under the heading A tragic celebration.

I wondered why this episode would leave such an indelible impression on my mother and I’m convinced it was because she saw the effect it had on my Gran. There’s no doubt that Mrs Hennigan and my Gran were friends. Both were Scots and recent immigrants to Western Australia. They had arrived in Wagin around the same time, worshipped at the local Catholic Church, had husbands serving in the AIF and were the mothers of young children. I can imagine that my Gran was very affected by this young mother’s death. Gran had been admitted to an Aberdeen orphanage when she was three years old and having grown into a very caring and compassionate woman, her heart would have gone out to the Hennigan children left motherless as she was, at a tender age. As often happens in country towns, the entire community came together. A subscription list was opened and the local Repatriation Committee organised and paid for Catherine’s funeral. My Gran and her three girls were listed among the mourners.

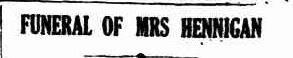

The tragic death of Mrs Hennigan during the celebrations in connection with the reported armistice on Friday of last week aroused universal regret and sympathy with the bereaved relatives. The funeral on Saturday afternoon was largely attended by her friends and many representative townspeople. Mrs Catherine Grace Hennigan was 32 years of age, and leaves two children, five and two years of age, her husband, being at the front. The deceased lady's father (Mr Walker) died somewhat similarly, and was a well-known temperance man in Glasgow, having been associated with the establishment of rooms which provided tea and refreshments for 2d in that town. The late Mrs Hennigan came to this State about seven years ago and was shortly after married to her husband, who came to Wagin about three years ago in the railway service. He enlisted on March 26th, 1917, and is now somewhere in France. The funeral ceremony was conducted by Father O'Reilly. The pall-bearers were Messrs Don Cronin, Keith Allport, Gamson (Returned Soldiers), Messrs King, Dick and Peden (Railway Department). A number of returned soldiers led the cortege, and a large number of soldiers' wives immediately followed. One of the largest gatherings seen for some time assembled at the graveside to pay their last tribute of respect to the deceased. Southern Argus & Wagin-Arthur Express. November 16, 1918 p2

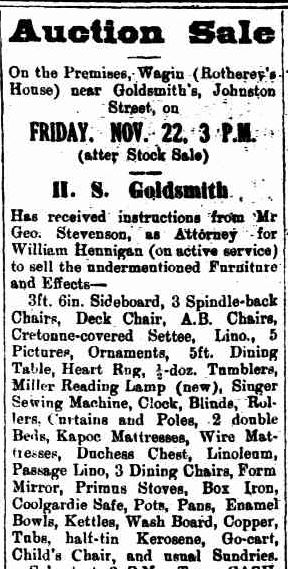

There was no mention of any care arrangements for her two children, Catherine Jnr. and Anthony. A George Stevenson, of Maylands, described as the attorney for Private Hennigan

It appears the townsfolk knew Catherine Hinnigan as 'Kathleen Hennigan'. How or why her surname was incorrectly spelt in newspaper reports and even in the local burial register and on the memorial stone erected over her grave will likely remain a mystery. Perhaps her broad Glaswegian accent had the locals confused and no one bothered to check. It’s also a mystery as to why it took three and a half months for Private Hinnigan to be repatriated back to Western Australia.

Nevertheless, in May 1919, Private Hinnigan or ‘Will’ as he was known, resumed his former job at Wagin with the Railways Department and a few years later, was promoted to the position of porter at Holyoake in the Dwellingup forest area.

Western Australia during the 1920s and 30s was aptly described as ‘a fine country to starve in’. One who was doing it particularly tough during those times was Amelia Lewis, mother of six and widow of State Sawmills employee William Lewis. Lewis had been tragically killed in an accident near Holyoake in May 1924.

BUSH TRAGEDY.

TRICYCLE COLLIDES WITH TRAIN. Timber Hands Killed.

Three deaths have occurred as the result of a terrible railway accident at a spot known as the six-mile bush landing on the timber mill branch line near Holyoake. Late on Tuesday afternoon William Lewis, Sydney Smith and E. Brogmus, employees of the State Sawmills, got aboard a motor tricycle and set off along the line. When they had travelled some distance, night came upon them. A howling wind arose, and rain commenced to fall, at first in showers and then in a tumultuous downpour. As the men proceeded on their way, some distance ahead of them a train, laden with a rake of logs ready for sawing, was puffing and panting along the line towards its destination, the timber mill at Holyoake. It summoned all its power to cope with a steep incline, but, when near the summit, it came to a standstill. Soon afterwards there was a sudden shout of dismay, followed by a splintering crash, and hoarse agonised screams. When the timber -train commenced its ascent of the steep gradient, the tricycle had just reached the top of the hill behind. The mill hands must have been unaware that the train was such a little distance ahead of them, and were apparently travelling at a high rate of speed when they suddenly perceived the rear trucks of the stationary train looming up out of the darkness. Their tri-cycle dashed into the train and was smashed to atoms, and in the space of a few minutes, the three men had breathed their last. Their injuries were terrible. A police constable and a medical man from Dwellingup went to the scene of the tragedy by a special train, and the bodies were taken to the mortuary at Dwellingup. An inquest has been ordered. The victims of the tragedy were married men with children. Their untimely end is the more to be regretted in that they were regarded by their employers as excellent workmen, and were highly respected in the district. The bare facts of the disaster were conveyed to the Government railway authorities yesterday, but, owing to the smash having occurred on a timberline, no detailed report was forwarded. The West Australian 22 May 1924, page 8

In a small town like Holyoake, there’s little doubt that Will Hinnigan knew William Lewis and his family and we can only guess how events played out. Will was transferred from Holyoake to York in late 1926 and two years later, in 1928, he and Amelia Lewis, now both in their forties, each widowed in tragic circumstances with eight children between them, married and eventually settled with their combined families in West Leederville. Ahead of them was the Great Depression and another World War.

This story started and ends with 32-year-old Scottish immigrant and young mother Catherine Grace Hinnigan (nee Walker). Although her husband was overseas fighting a cruel war, she, like most women on the Home Front, dealt as best she could with the consequences of that terrible conflict. She cared for her children alone, feared for their future as well as the safety of her husband and sadly was never to know the joy of his homecoming.

On this Centenary of the Armistice, we also remember those who ‘kept the home fires burning’, and those who waited… sometimes in vain.

NOTE: I am indebted to Darcey Yates from the Shire of Wagin for her speedy response to my request for an image of Catherine Hinnigan's grave. The Shire of Wagin is hereby gratefully acknowledged for their contribution to this story.